When Namibia stunned me

An African country without a strong leader that has managed to avoid the pitfalls of its contemporaries

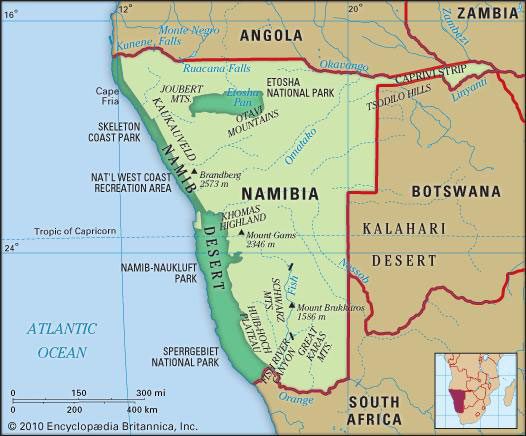

THE LAST WORD | Andrew M. Mwenda | The Batooro have a saying: akaana katabuunga katekereza ngu nyinako nuwe acumba ebinura (a child who has not travelled thinks the mother is the best cook). That saying came to my mind when visiting Namibia this week. It looks and feels like a developed country. Its capital city, Windhoek, and its coastal city, Swakopmund, are not different from a midsize city in France, Netherlands and Sweden in the quality and neatness of infrastructure – roads, shops, hotels, etc. Driving around the country, one is struck by the quality of its roads. For instance, the highway from Windhoek to Swakopmund is similar to highways in rich countries of Europe.

Yet Namibia got independence over 35 years ago. Unlike other African countries, the coming of Black/majority rule has not led to the disintegration of the state and its efficiency and effectiveness. This is similar to the experience of Botswana, which, since independence, has enjoyed stability, peaceful regular elections, an efficient and effective bureaucracy, and sustained and accelerated development. In fact, Botswana is more developed than Namibia. I used to think Botswana’s success was a result of a limited colonial imprint. The British were not interested in this colony, so much so that they governed it from a small town in South Africa.

For the rest of Africa, the period after independence led to a rapid collapse of administrative effectiveness. Some countries built on the colonial legacy and ensured a growing economy and improved quality of life for a few years and then disintegrated into neo-patrimonial mismanagement: Kenya until 1982, Ivory Coast until 1990, Uganda until 1970, etc. By 1990, most countries in Africa had entered a period of disaster – coups, civil wars, high debt, economic stagnation or collapse, etc. Botswana, Mauritius, Seychelles and Cape Verde were the exceptions. Indeed, South Africa has proved the same path. Its good road infrastructure, big cities and large economy have not stopped the neighbourhoods from becoming sprawling garbage dumps and crime to be high.

But let us go back to Namibia. It is a large country by land size, 840,000 square kilometers compared to Uganda’s 248,000 square kilometers. However, it has a population of only 3m people compared to Uganda’s 46m. According to Geoffrey Herbst, in his book, States and Power, such large geographical reach with a small population makes it very expensive for states to broadcast power, thereby undermining the evolution of strong and effective states. Therefore, Uganda should have a more effective state than Namibia. Yet Namibia has a GDP of $14.2 billion, according to the IMF, while Uganda $64 billion. In terms of per capita income (total income divided by total population), Namibia’s stands at $4,700 while Uganda’s stands at $1,350.

However, these nominal figures tell us little about the size of an economy. The real measure is Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), i.e., the actual basket of goods and services nominal dollars can buy. For instance, if I earn $1,000 in Kampala and someone else earns the same amount in New York, can we buy the same things? Certainly, what $1,000 buys in Kampala may need $5,000 to buy in New York. Namibia’s GDP in PPP is $38 billion against Uganda’s $187 billion. In per capita income terms, Namibia stands at $12,400 while Uganda is at $3,900.

These numbers are important because they tell us the capacity of the state to provide public goods and services to its citizens. The higher the per capita income, the higher is likely to be the revenue per person (total tax revenue divided by the population) and hence the public expenditure per person (total government spending divided by the total population). Uganda’s per capita revenue is $205 while her per capita public spending is $323. For Namibia, public revenue per person is $1,700 and public spending per person is $2,000. Holding other factors constant, it follows, therefore, that government in Namibia has four times higher capacity to serve its citizens than Uganda.

Yet these numbers and arguments do not absolve the government of Uganda from its gross incompetence and disregard for the public good. Namibia has sustained high levels of administrative competence, thereby making it possible for the state to deliver a large basket of public goods and services effectively and efficiently to its people. I think this is because SWAPO, the ruling party, has sustained its moral purpose, while the NRM in Uganda lost it. Instead, NRM degenerated into a cash-and-carry government where everyone is out there to serve their personal interest. The marketisation of the economy in Uganda went hand in glove with the marketisation of politics.

Advocates of Uganda can point out the numbers of GDP and per capita public spending to argue, and legitimately, that I am being unfair to the NRM. Namibia, as seen above, spends $2,000 per person compared to Uganda’s $325. Uganda’s problem is Rwanda. It has the same public spending per capita as Uganda. Yet its infrastructure rivals that of counties 20 times richer. Why? Because the RPF has sustained its moral purpose – to serve the public good. Ethiopia has similar public spending per person as Uganda, yet its infrastructure rivals that of Namibia, Botswana and Rwanda. Therefore, it’s not the available resources that make Uganda’s road infrastructure a disaster. It is the sheer indifference, incompetence, lack of a moral purpose within the state and lack of responsiveness to the public good that explains the difference.

Let me illustrate: since COVID in 2020, President Yoweri Museveni has taken to using Kololo Independence Grounds regularly for his meetings. When there, he blocks all roads and around. Traffic is diverted to York Terrace, then Prince Charles Drive, on to Elizabeth Avenue. All these three streets in Kololo are narrow and in a sorry state, clogged with potholes. So cars get clogged, causing severe traffic jams. For five long years, no one in KCCA or the government has found it important to solve this serious problem, whose cost would not be even a million dollars.

What explains this indifference? It is right to blame Museveni. But what of the KCCA? Would Museveni fire the ED if they tried? What of the minister of finance and his permanent secretary/secretary to the treasury? Assuming they allocated that paltry $1m in the KCCA budget to solve this tiny problem, would Uganda’s budget of $15 billion collapse? Something is gone wrong in our state and society that we need to think seriously about.

***