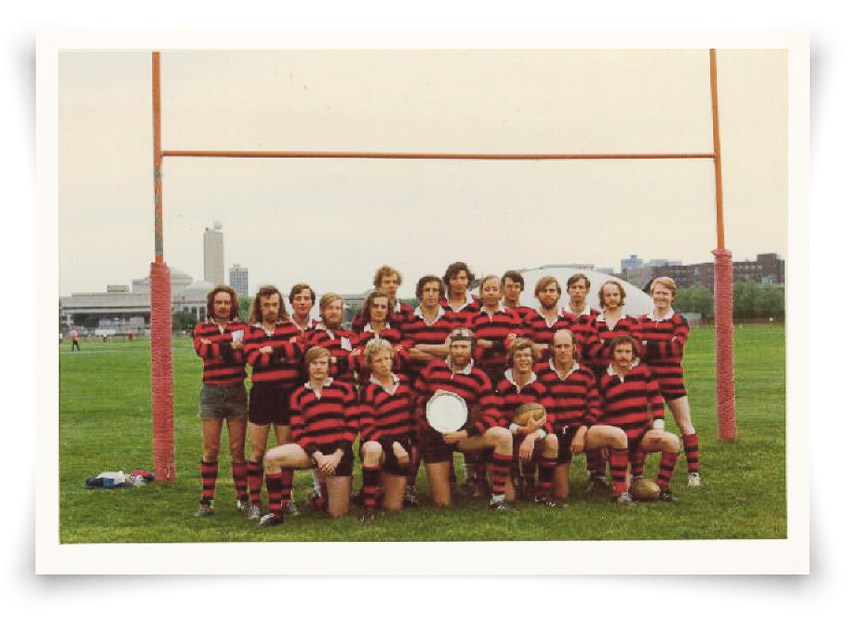

The silver-platter season

In the spring of 1974, I was new to both MIT and rugby football. As a Course 2 graduate student, I shared a basement office with several other students, including two players on the Tech rugby club who encouraged me to join them. Being both an Anglophile and a beer drinker, I was pretty easily…

In the spring of 1974, I was new to both MIT and rugby football. As a Course 2 graduate student, I shared a basement office with several other students, including two players on the Tech rugby club who encouraged me to join them. Being both an Anglophile and a beer drinker, I was pretty easily talked into participating in this sport, with its British roots and after-match parties.

I played mainly on the squad’s B side that season but was among those asked to join the A side players in the annual tournament of the New England Rugby Football Union (NERFU), held at UMass Amherst. We needed extra men for the exhausting tournament schedule, in which players from both the A and B sides would be combined in various ways for different matches. Today NERFU has many more teams and several divisions of competition. But in 1974 it had just one division and held a single annual tournament.

Institute records show rugby being played as early as 1882, making the Tech club the oldest in NERFU and one of the oldest in the nation. In 1974, it fielded two 15-man sides that practiced twice a week and played every Saturday during the spring and fall seasons. (There was no women’s side then.) Our school-supplied uniforms were classics of a bygone era—striped long-sleeve jerseys with collars and rubber buttons.

Rugby matches are grueling affairs involving continuous running and tackling and (for forwards like me, who make up half the team) pushing in organized scrums and ad hoc rucks. (In both scrums and rucks, players grab teammates’ shirts, binding together to push against the opposing team while attempting to gain possession of a ball on the ground with their feet.) In 1974, substitution was allowed only in cases of injury. Usually, one match per week was all a player would play. Making it to the tournament’s championship match would require playing four or five in two days, so some players would need to sit out some of the matches.

Unlike now, in the 1970s there were few (if any) US high school or under-19 rugby teams, so American college teams were generally inexperienced. However, the 1974 MIT club had several international players who had been playing since grade school in England, Scotland, New Zealand, France, Argentina, or Japan. It also included grad students and an assistant professor (Ron Prinn, ScD ’71), which raised the average age of the team. MIT was thus not a typical college team, although we might have been mistaken for one. Undoubtedly some club teams in the 1974 tournament rested their best players when scheduled to play us.

Our coach was Serge Gallant, a savvy, bearded Frenchman and former scrum half forced by concussions to retire from playing. Shin Yoshida ’76, our fly half, was our star player. Shin would kick high-arching punts downfield, accurately positioned to allow our team to immediately tackle opponents receiving them, or occasionally to recover the ball ourselves. Much like a fast-break offense from a basketball team with smaller players, this helped neutralize the height and power of bigger teams.

The 1974 NERFU tournament, held on May 11 and 12, pitted 24 teams against each other in five rounds of single-elimination matches. The MIT club had some role in the seeding, so we managed to get a first-round bye and the prospect of an easy opponent in the second round. However, the remaining matches promised to be very difficult.

Our first match on Saturday was in the second round against Springfield, whom we beat handily, 13–0. Our last match of the day was against Charles River, a club that had beaten us the week before. We eked out a 16–12 victory in double overtime.

Since we’d advanced to the semifinal round to be held on Sunday, arrangements were made for our team to pile into a few rooms of an Amherst motel for the night. But first most of us went out to a local restaurant. Despite our camaraderie and shared joy over having won our first two matches, our celebration was subdued, with none of the usual libations and rugby songs. We were pleasantly surprised when a former MIT rugby player turned businessman pick up our meal tab.

At the restaurant we exchanged friendly banter with a well-known forward on the Providence city club, our next opponent. During the meal he playfully growled at us while chomping on a handful of spring onions. However, he did not play against us in the semifinals on Sunday. He was rested for the finals match he never got to play.

During the Providence match, their sideline people kept yelling “Get the foot,” meaning to target Yoshida and take him out of the game. But our “enforcers” took care of theirs, and he was not hurt. We went on to win, 6–3.

I had played in the third- and fourth-round matches and was exhausted. So when our coach asked me to play in the finals, I begged off. My spot was taken by Mark Sneeringer ’76, PhD ’82, an amiable sophomore from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Because I wasn’t playing, I was picked to serve as a line judge.

For the championship match Tech faced off against the Beacon Hill club, which had won the year before. This was another tight and grueling game that went into double overtime. In the first overtime, our forwards were gasping for breath. Roger Simmonds, PhD ’78 (an Englishman and our most experienced player), lifted spirits and energy levels with an impromptu pep talk noting how well the forwards were playing and how worn out the Beacon Hill squad was.

In the second overtime, team captain Paul Dwyer, SM ’73, finally scored the game-winning try. Because I was a line judge, my jumping for joy with a cloth in my hand caused temporary confusion. That was soon resolved when I explained that my action was not an officiating signal. We’d bested Beacon Hill, 7–3.

Our reward for winning the championship was a silver platter. In those days, beer was always on hand after rugby matches, so while still on the pitch, we awkwardly drank beer from the platter as if it were a trophy cup.

Having pulled off a major upset in the NERFU tournament, MIT was no longer a dark horse in the 1974 fall season, and other teams made sure to give us their best efforts. The loss of Yoshida, Dwyer, and other key players from the spring season weakened our fall A side, to which I was promoted. We began the fall season with two wins and two losses and then lost the rest of our matches, including one in which the Boston club thoroughly overpowered and crushed us.

Nevertheless, Tech reigned as the NERFU champion until the next tournament. NERFU would eventually add a college division to its annual competition, so to this day, MIT’s rugby club remains the only college side ever to capture the top-tier NERFU title.

After retiring from a long career in mechanical and nuclear engineering, Dan Guzy, MechE ’75, has written four books and many articles on local history.